image: Fashion Nova

The fashion pack loves the idea of cultivating a uniform. Whether it is Vogue’s documentation of “Parisian Uniform Dressing,” WhoWhatWear’s offering of “7 Style Uniforms Fashionable Women Swear By,” or the ManRepeller’s asking, “Is Uniform Dressing the Nirvana of Personal Style?,” it is clear that committing to wearing variations of a few key garments and accessories – or “uniform dressing,” as it has come to be known – is not only a very convenient and oftentimes one of the more sustainable ways to dress and shop, it is also the method du jour of the world’s most stylish.

French style icon Ines de la Fressange, for instance, “has become almost synonymous with her daily uniform, a simple but polished combination of high-waisted cropped trousers, white top, light jacket, and flats,” according to Vogue. This sartorial practice is, wrote the magazine’s Liana Satenstein, “the epitome of personal style.”

But what happens when that wardrobe, or uniform, is the same as everyone else’s? While dress was for centuries – and for many, still is – a way to distinguish oneself from others, the homogenization of fashion across the spectrum (from fast fashion to high fashion) is a very real phenomenon, one that has at least some strong roots in the rise of the internet and social media. Platforms, such as Instagram, for instance, make it easy for brands and fashion publications to engage with consumers and extol (i.e., sell) their seasonal trends upon willing audiences, who are not merely social media users, but are consumers, too, after all.

All the while, these platforms connect individuals, whether it be influencers, celebrities, or just regular old fashion enthusiasts, who, with their own imagery – whether it is paid for (#ad) or not – tend to further create momentum and fuel the cyclical nature and power of fashion trends.

Fast fashion brands – with the utter expansiveness of their geographic footprints and the otherwise unheard of price points of the garments supplied as the basis of their high-volume turn over model – have pushed the notion of trends, which for many years were largely off limits to anyone other than high fashion consumers, to entirely new heights.

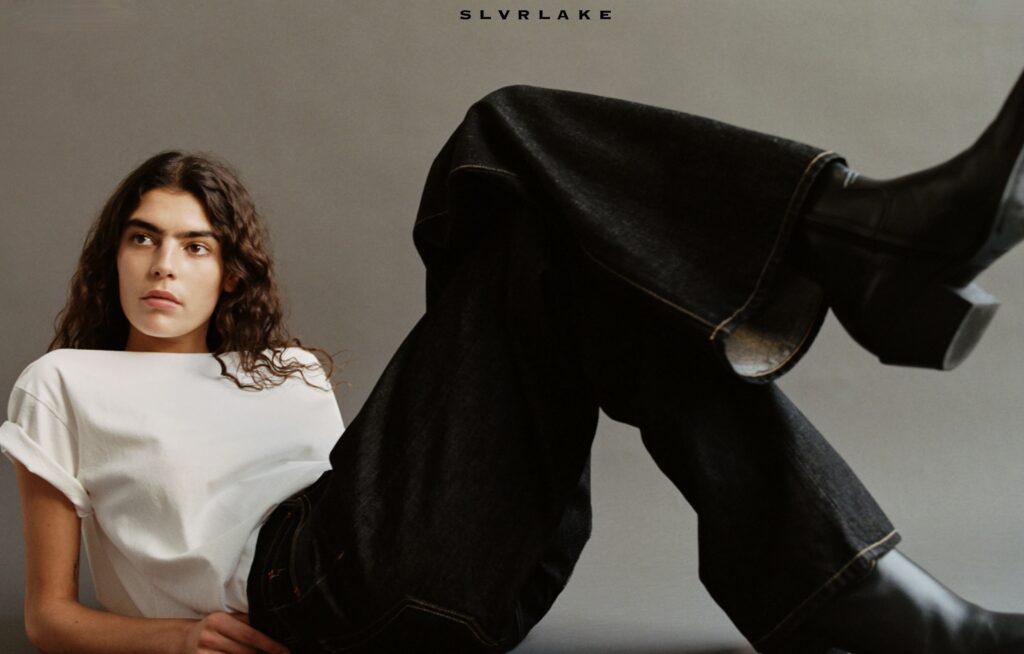

This is where Fashion Nova comes in. Describing itself as the home of “cheap & affordable fashion online,” including “sexy club dresses, jeans, shoes, bodysuits, skirts and more,” the Los Angeles-based brand is one of the more widely-known fashion phenomena of the moment. Founded in late 2006, Fashion Nova, which maintains a handful of brick-and-mortar stores, packs most of its punch by way of its e-commerce site, where it adds up between 600 and 900 new styles every single week.

“To paying customers, especially hard to fit ones,” writes the Associated Press, “Fashion Nova symbolizes a revolution in terms of access to trendy, affordable clothes.” That revolution has seen the brand build a truly massive social media presence and a level of buzz that enabled it to nab the position of the fourth most-searched-for fashion brand in the U.S. for 2017, according to Google’s “Year In Search” ranking.

With such wild success comes the potential of downside, of course. The problem with Fashion Nova, Texas YouTuber Ose Prather, 31, told the AP, is this: “All of these girls are beginning to look like clones of each other. They have long, flowy hair, they got Kylie Jenner lips … They all have the same outfit on.”

In short: “All y’all look the same. All y’all dress the same,” she says.

And this may be true. In fact, it likely is true given that this practice existed long before Fashion Nova – and given the widespread reliance of high fashion on trend forecasting services and trends, in general – it is not in any way limited to Fashion Nova. The retailer just happens to be the one that is servicing one of the largest groups of people right now, and as a result, cloning them to its aesthetic.

It was not that long ago, that everyone looked more or less like a clone of Phoebe Philo’s Celine models, thanks to Zara consistent churning out of Celine-inspired garments. The same can routinely be said of Kanye West’s Yeezy, which saw fans (and non-fans, alike) racing to e-commerce sites to stock up on monochrome casualwear, including olive green crew neck sweatshirts and distressed beige tees.

At its core, what Fashion Nova is doing is tapping into fashion fans’ age-old desires to show that they are worthy, that they are in the know, that they are cool. The result of this is, of course, uniformity.

As psychologist Emily Lovegrove told The Telegraph in 2015, this “herd mentality” when it comes to garments and accessories is part of a larger “survival mode” tactic, which she says “affects our wardrobe choices beginning in childhood.” This becomes particularly common when individuals become secondary school age: “You desperately want to fit in with what [your peers] like because kids who look different are the ones that get picked on,” she states.

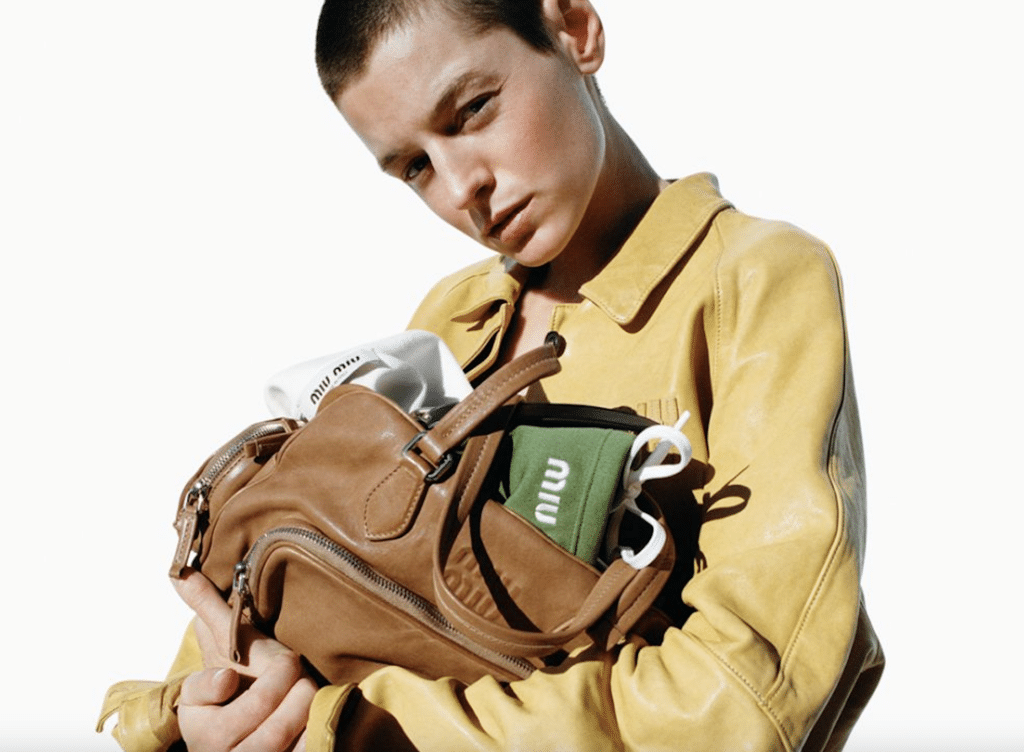

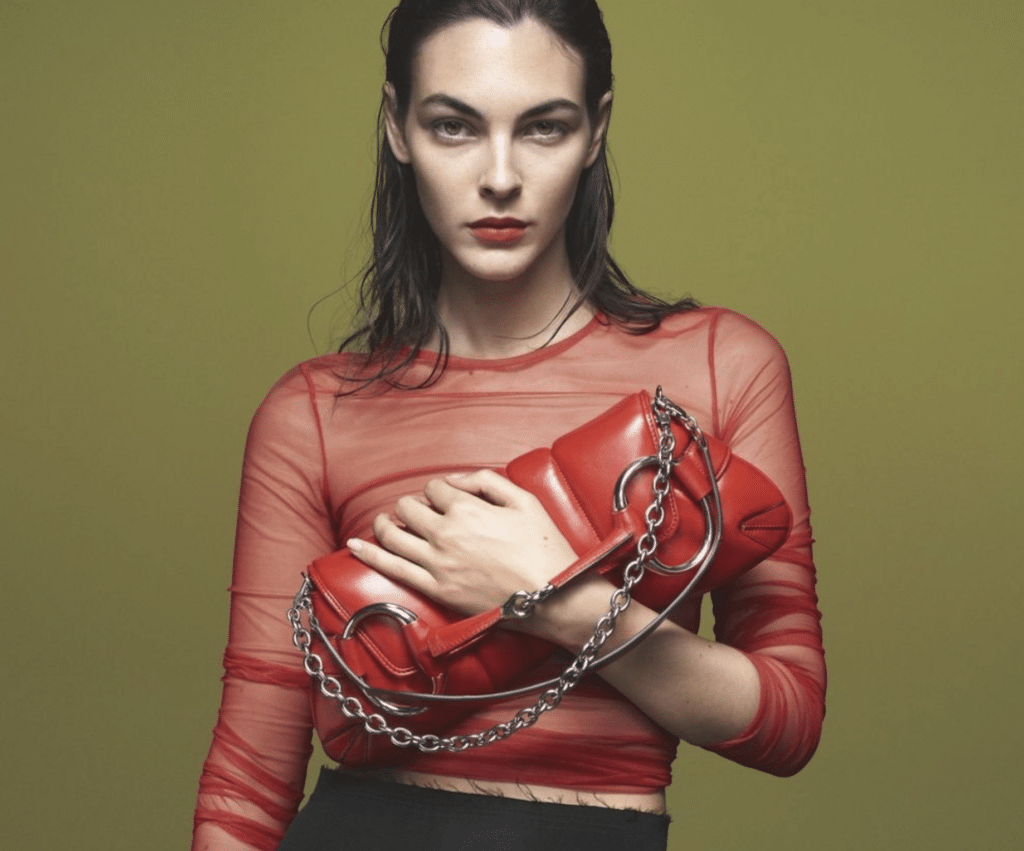

This sense of wanting to “fit in” does not leave us when we leave grade school; it carries on (and in some cases, maybe even intensifies in light of social media and the accessibility of disposable fashion) into later life. In many instances, it is paired with the use of signifiers of status, whether it be an “it” bag or the wares of a particularly coveted streetwear brand, both of which tend to result in widespread purchases across big groups of people, most of whom are driven by a similar desire to fit in, for one reason or another.

This is also not a particularly novel practice, especially since for quite a while now, most consumers have taken to purchasing garments and accessories – with greater regularity and in greater volumes – not because fashion is particularly relevant or engaging, but because they know what is “in” and they want to keep up with appearances.

It just turns out that since everyone, Fashion Nova included, has access to the same sources of trend-facilitating media, whether it be Selena Gomez’s Instagram account or Kim Kardashian street style photos – those “appearances” that we all went to keep up, tend to look more and more like everyone else’s. Mission accomplished?