The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld a lower court’s decision in a trademark case that pits Warby Parker against 1-800 Contacts, Inc. In the underlying lawsuit, which was filed in a New York federal court in August 2021, 1-800 Contacts accused Warby Parker of running afoul of the law by using 1-800 Contacts’ trademark-protected name as a search engine keyword and adopting a website that allegedly “mimics the look and feel of 1800contacts.com.” In its October 8 opinion, a panel of judges for the Second Circuit affirmed the lower court’s finding that simply purchasing a competitor’s trademark as a keyword does not, by itself, amount to trademark infringement.

In June 2022, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York sided with Warby Parker after finding that 1-800 Contacts had not plausibly plead its trademark infringement and unfair competition claims, namely, because it failed to show that consumers are likely to be confused as to the nature of Warby Parker’s products. In its appeal, 1-800 Contacts alleged that consumers are, in fact, likely to be confused by Warby Parker’s scheme to purchase its trademarks in search engine keyword auctions and its use of “misleading paid advertisements, so that customers searching for [the 1-800 Contacts’] website … would be diverted to [Warby Parker’s] website instead.”

Keyword Bidding is Not Infringement

The Second Circuit upheld the Southern District of New York’s ruling, stating that “[w]e now reiterate that the mere act of purchasing a search engine keyword that is a competitor’s trademark does not, alone, in the context of keyword search advertising, constitute trademark infringement.” In its decision, the court explained that Warby Parker’s ads, while triggered by searches for 1-800 Contacts’ trademarks, did not create a likelihood of consumer confusion since Warby Parker’s branding was clearly visible on its ads and its website. Furthermore, the court stated that Warby Parker’s advertisements did not use 1-800 Contacts’ marks in the actual ads or on the landing pages that consumers were directed to after clicking.

“[1-800 Contacts] does not claim that [Warby Parker] actually used the former’s trademarks other than purchasing them as keywords in the online search engine auctions,” the court clarified.

Considering 1-800 Contacts’ likelihood of confusion claims, the court applied the eight-factor Polaroid test to determine whether Warby Parker’s use of its trademark is likely to confuse consumers. Among some of the court’s determinations on the confusion front are …

> Similarity of the Marks: The court emphasized that Warby Parker’s ads were clearly labeled with its name and domain prominently displayed. “Warby Parker’s name was clearly displayed in both the paid Google advertisements and the Deep Linked Ad Page,” the court explained. As a result, it concluded that “it was not plausible for reasonably sophisticated internet consumers to be confused as to whether they ha[d] navigated to, and [were] purchasing contacts from” 1-800 Contacts or Warby Parker.

> Actual Confusion: 1-800 Contacts did not provide evidence of actual confusion, such as consumer surveys or testimonials, the court stated. The court found that 1-800 Contacts’ allegations of confusion were “conclusory at best” and that “a complaint’s conclusory statements without reference to its factual context” are insufficient to establish actual confusion.

> Bad Faith: While 1-800 Contacts argued that Warby Parker had acted in bad faith by bidding on its trademarks, the court concluded that this factor, on its own, did not prove infringement and that “the dissimilarity of the marks factor is dispositive in this case.”

As part of its confusion claims, 1-800 Contacts also argued that Warby Parker’s keyword bidding caused “initial-interest confusion,” which refers to situations where consumers may be initially misled by the use of a competitor’s trademark but realize the true source of the product or service before completing a purchase. The court rejected this argument, explaining that Warby Parker’s advertisements were clearly labeled and did not deceive consumers.

The court noted that “we require a showing of intentional deception to sufficiently plead internet-related initial-interest confusion.” The panel of appeals judges further stated that “consumers diverted on the Internet can more readily get back on track than those in actual space.”

Warby Parker’s Website Design

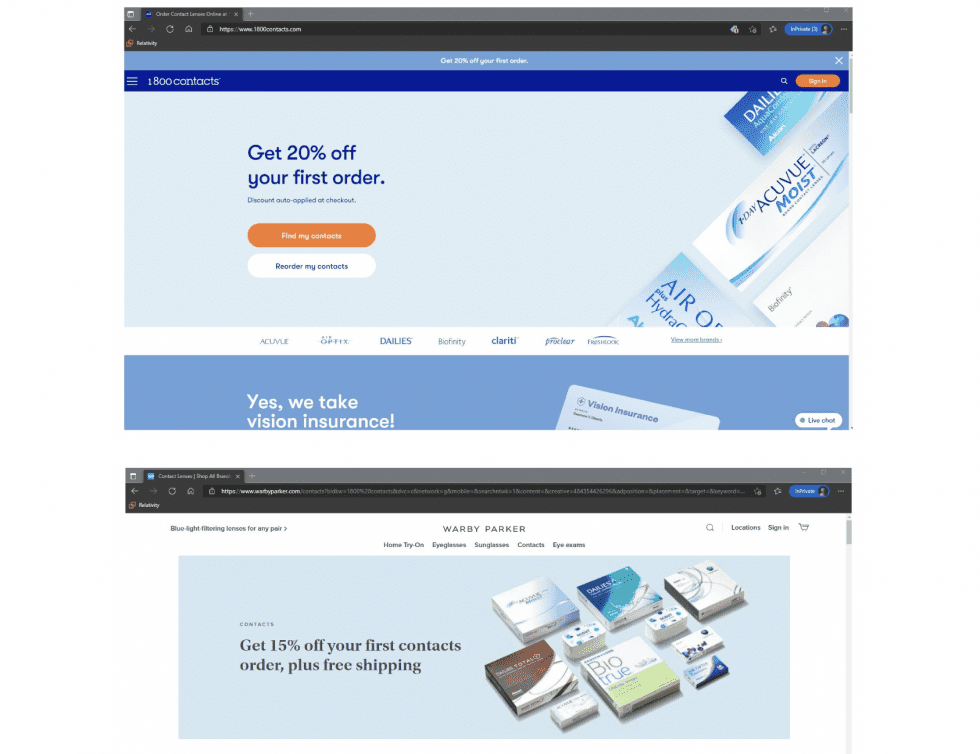

Not limited to the keywords in play, 1-800 Contacts also asserted that Warby Parker’s landing pages mimicked the look and feel of its website, which served to further confuse consumers. This includes “use of a confusingly similar color scheme, layout, and discount offering, along with imagery evoking the 1800contacts.com website,’ such as by using a ‘familiar light blue colored background displaying representative contact lens products and a discount offer, just like that found at 1800contacts.com.’”

However, the court ruled that 1-800 Contacts was out of luck with that argument since the company “did not plead or argue that the ‘look and feel’ of its website is a protectable mark.” Delving into 1-800 Contacts’ trade dress infringement arguments, the court compared screenshots of 1-800 Contacts’ and Warby Parker’s websites and found that Warby Parker’s branding was prominently displayed on its site. And while both websites used a light blue rectangular box and discount offers, the court concluded that those similarities were not enough to confuse consumers.

“A comparison of the website screenshots does not lead to a plausible inference that ‘an appreciable number’ of consumers … would actually be confused,” the court stated.

Sophistication of Consumers

Finally, the court also addressed another element of the Polaroid test: consumer sophistication. In noting that internet users are generally sophisticated enough to recognize the difference between competitors, especially when ads are clearly labeled, the court stated that “[e]ven assuming that some consumers will mistakenly click on a Warby Parker paid search result and inadvertently navigate to Warby Parker’s page, these consumers would then take time to meaningfully review the contents and layout of the website before taking any further action.”

Still, the court ultimately agreed with 1-800 Contacts on this factor, finding that the District Court had gotten it wrong in assuming the customer base was “reasonably sophisticated” because the court had assumed facts outside of the complaint, according to the decision. However, since the appellate court viewed “the Polaroid factors as a whole,” it found that 1-800 Contacts’ complaint “fails to plausibly to allege that consumers are likely to be confused by any portion of Warby Parker’s search advertising plan.”

Warby Parker’s lead counsel, G. Roxanne Elings of Davis Wright Tremaine, told TFL on Tuesday that the company was pleased with the result. “We are delighted that the Second Circuit has now joined the consensus in affirming the purchase of adwords like those asserted here by the plaintiff do not arise to trademark infringement,” Elings said.

A representative for 1-800 Contacts was not immediately available.

The case is 1-800 Contacts, Inc. v. Warby Parker, No. 22-1634 (2nd Cir.).