The definition of “investment” within the fashion sphere has evolved. So-called “investment” pieces used to refer to timeless, often high quality garments and accessories worth spending more on with the intent of keeping them in your wardrobe for longer. It was an apparent shift away from fleeting trends and the breakneck pace at which fast fashion brands, in particular, churn out endless offerings. More recently, “investment” pieces has come to mean something else entirely, particularly when it comes to certain handbag styles: The term is being used to describe accessories that are part of a class of investment assets, or in other words, handbags that are purchased for the sole purpose of earning returns when they are later resold.

The idea of using a handbag as an investment gained mainstream attention back in 2016 when Baghunter released a report that charted returns for Hermès’ Birkin bags from 1980 through the end of 2015 and compared them to returns derived from the S&P 500 and gold during the same 35-year period. Declaring Birkins a better bet than the two more traditional investment avenues, Baghunter found that while stock market gains and the value of gold are subject to “normal increases and decreases,” the value of Birkin bags only increased. In fact, the Beverly Hills, California-based luxury handbag reseller stated that the Hermès bags were continuing to grow in value – by an annual average of 14.2 percent. In other words, Birkins, which retail for upwards of $10,000 (subject to additional hoops/spending), do not have bad years, making them “the safest and least volatile investment market of the three,” per Baghunter.

Two years later, Jefferies analysts lent some credence to the notion of “investment” bags, citing the “strong secondary market” for certain items within the luxury sector, namely, Hermès’ most coveted handbags. In particular, the analysts cited the sale of “one Himalaya [Birkin bag] bought in 2010 for 29,600 euros, which was sold – as a pre-owned bag – six years later for 157,500 euros.” That represents a “432 percent upswing against about 310 percent if one had bought a Hermès share at the beginning of 2010 and sold it at the end of 2016.”

In yet a further nod to the budding power of alternative assets like luxury handbags, stalwart auction houses have introduced categories that include handbags. London-headquartered Christie’s, for example, started toying with online-only auctions of designer handbags in 2012, and by 2017, had established a standalone “Handbags & Accessories” category that had transitioned from an online-only experiment to a record-breaking segment.

The Potential Fallacy at Play

There may be some consensus that luxury goods “can sometimes hedge against inflation when they appreciate in value,” as Bay Street Capital Holdings founder William Huston told MarketWatch this summer. However, the prospect of handbags as assets is not without nuance, particularly when compared to things like the S&P 500 and gold ETFs and futures, and it is not without skeptics. In short: The prospectuve gains at hand may not be a straightforward as saying that the rising value of Birkin bags will necessarily outperform the general stock market.

Some significant differences exist between the markets for luxury handbags and those for more traditional investments, making for uneven comparisons. Primarily, the size of the market for the stocks of publicly-traded companies drastically outweighs the market for assets like Birkin bags. Companies, such as Amazon or Apple, for instance, have average daily trading volumes of upwards of 50 million, respectively, whereas there are an estimated one million Birkin bags in existence – and only a fraction of them are being offered up for resale. As Sapna Maheshwari previously wrote for BuzzFeed News, “Thanks to the size of the stock market, if Apple shares are priced at $100 each, that is the price you will be able to buy or sell them at. There is no such guarantee when it comes to rare handbags.”

Put another way, the relatively small number of active participants in the Birkin and Kelly resale market – most of whom trade relatively infrequently – makes for a market of low liquidity. (The same is also true of the size of market for more common luxury bags, such as Chanel Flap bags and Louis Vuitton Neverfulls, compared to the market for equities.)

Another issue, according to Maheshwari, is the fact that the demand – and thus, the market – for the most coveted Hermès bags is built on (and is heavily dependent upon) the notion of exclusivity, and as a result, the market is subject to diminishing value in the event that consumers no longer see these offerings as the holy grail of handbags. This is true. And while the relatively easy availability of authentic Birkin and Kellys thanks to the advent of resale websites like The RealReal and the rise of “super fakes” could be chipping away at the Birkin bag mystique to some extent, this argument also applies to companies like Apple. As a consumer-facing company, Apple, for instance, is not immune to the potential that it would lose value if its brand – and the products bearing its branding – becomes less popular; after all, no small part of what Apple is selling is its brand, which also occupies luxury positioning.

However, the difference between a hypothetical drop in demand for Apple and diminishing demand for Hermès bags is a big one, as the size/liquidity of the market for Apple would make it is very easy to sell off an Apple stock-holding position in such a situation. The same cannot be said for Birkin bags.

Still yet, there are other issues that make luxury “investment” assets – i.e., Birkin or Kelly bags – more unpredictable than traditional securities. There is the undeniable risk that these goods “could get lost or destroyed, or may otherwise be difficult to resell,” Huston maintains.

A Growing Market, Nonetheless

Despite these difficult realities, the notion of investing in handbags has not lost steam. Bloomberg recently reported that “with the stock market roiling, luxury goods – especially designer handbags – are becoming a hotly sought-after investment commodity.” The publication cited a June 2023 report from Credit Suisse – which showed that certain Chanel bags rose in value 24.5 percent year-over-year – as evidence of the power of some of the assets in this area. At the same time, Knight Frank similarly revealed in its 2023 Wealth Report that investments in luxury handbags are on the rise.

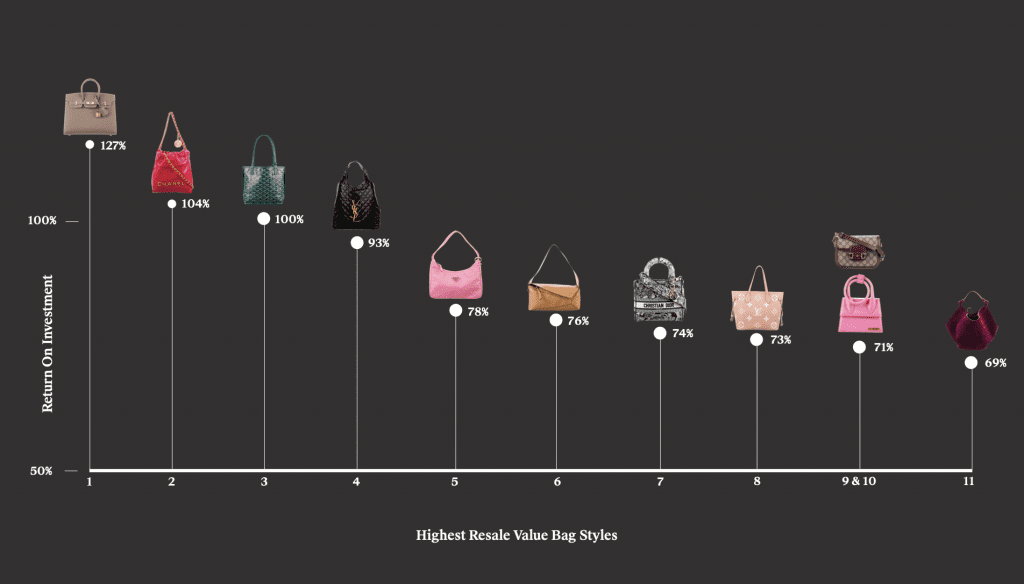

All the while, The RealReal’s annual Resale Report, which was released in August, confirmed that “return on investment is not limited to Hermès bags.” In fact, aside from Hermès Birkins (which retain 127 percent of value), the handbags that currently boast “the best resale value, or return on investment” are Chanel 22 (retains 104 percent of value), Goyard Mini Anjou (retains 100 percent of value), Saint Laurent Icare, Prada Re-edition, Loewe Puzzle, Dior Lady D-lite, Louis Vuitton Neverfull, Jacquemus Le Chiquito, Gucci 1955 Horsebit, and Khaite Lotus.

In the same report, The RealReal lists Hermès bags as having the overall highest resale value, followed by Chanel and then Louis Vuitton bags. (Regarding Chanel’s Classic Flap bag, which is widely regarded as among the holy grail of investments, it was the “#1 most searched-for bag” and #1 most purchased bag” across generations of consumers this year, according to The RealReal’s report. At the same time, sales for the bags reached “record” levels “following primary market price increases,” the reseller revealed.)

This is, of course, good news for brands. For one thing, brands almost certainly benefit in the form of sales from the narrative that their offerings can be used not only as accessories but as investment pieces. It is also somewhat well-established that luxury companies stand to gain when consumers know that the products they are buying may retain (some meaningful portion of) their value and can be resold later; in fact, it has been proposed that a robust resale market for luxury goods increases consumers’ willingness to pay more for luxury goods – which is convenient given that no shortage of brands have aggressively looked to boost prices in recent years

And beyond that, as Bernstein’s senior global luxury goods analyst Luca Solca stated in a note this summer, “the emergence of the second-hand market further reinforces category consolidation and mega-brand concentration, as it provides instantaneous and transparent evidence of which brands hold value and which don’t, [which] is bound to push middle-class consumers to converge even more to ‘surefire’ brands.”