Deep Dives

The European Union has been at the forefront of sustainability-centric regulation in recent years amid the enduring growth of “green” products and services, and a spike in environmental, social, and governance (“ESG”) reporting by companies in connection with their corporate strategies. As companies look to cater to increasingly eco-conscious consumers and investors, there is an undeniable “trust deficit” that comes with “the broad scope for misleading claims” at play in the climate realm, according to Travers Smith LLP attorneys.

Because of the complexity of the issues and the large-scale lack of uniformity (and cherry-picking) that accompanies voluntary ESG reporting and efforts to define terms like “sustainability,” it is “particularly difficult” for consumers, as well as investors, analysts, and other stakeholders, “to know whether to trust companies’ environmental claims,” they assert. And this is not helped by the fact that there is also “significant scope for [climate and other ESG] claims to be misleading.”

Against that background, lawmakers and regulators are aiming to implement legislation to bolster transparency about companies’ climate – and broader ESG – claims and credentials. In several key cases, the regulation comes in one of two key forms: (1) directives that aim to provide insight into companies’ operations by requiring them to conduct due diligence on climate/sustainability aspects of their business and disclose/report on those findings, and (2) bills that govern the “green” claims that companies make to consumers, investors, analysts, etc. about their products and/or services.

TFL takes a dive into a few pieces of reporting/disclosure-focused and marketing-centric legislation that are currently pending in the EU …

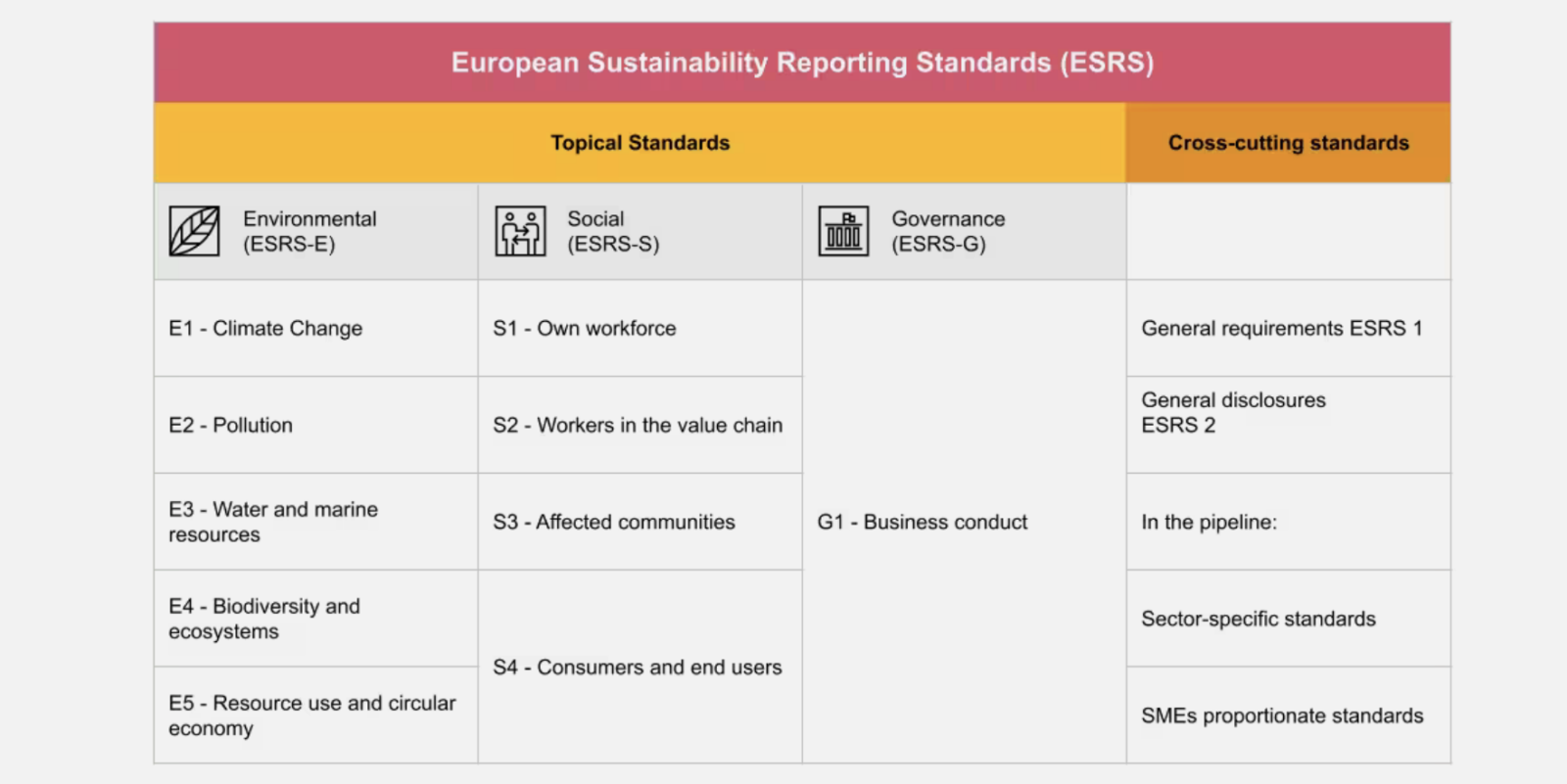

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (“CSRD”) – Introduced as part of the European Commission’s Sustainable Finance Package, the CSRD – which as its name indicates, emphasizes corporate reporting – endeavors to enable stakeholders to better evaluate companies’ sustainability performance, including corresponding business impacts and risks. The legislation requires EU businesses (and qualifying subsidiaries of non-EU companies) to report on the environmental and social impacts of their business operations, and on the business impacts of their ESG efforts and initiatives by way of disclosures prescribed by the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (“ESRS”).

Specifically, the CSRD requires companies to provide third-party audited reports that detail non-financial elements of their immediate operations, as well as those of their upstream and downstream supply chains. This means that “companies must invest more resources in relationships with their suppliers and integrate sustainability-related risk assessment into their purchasing decisions,” per Deloitte, which notes that the CSRD “will affect most industries, obliging companies to track emissions and report their reduction targets.”

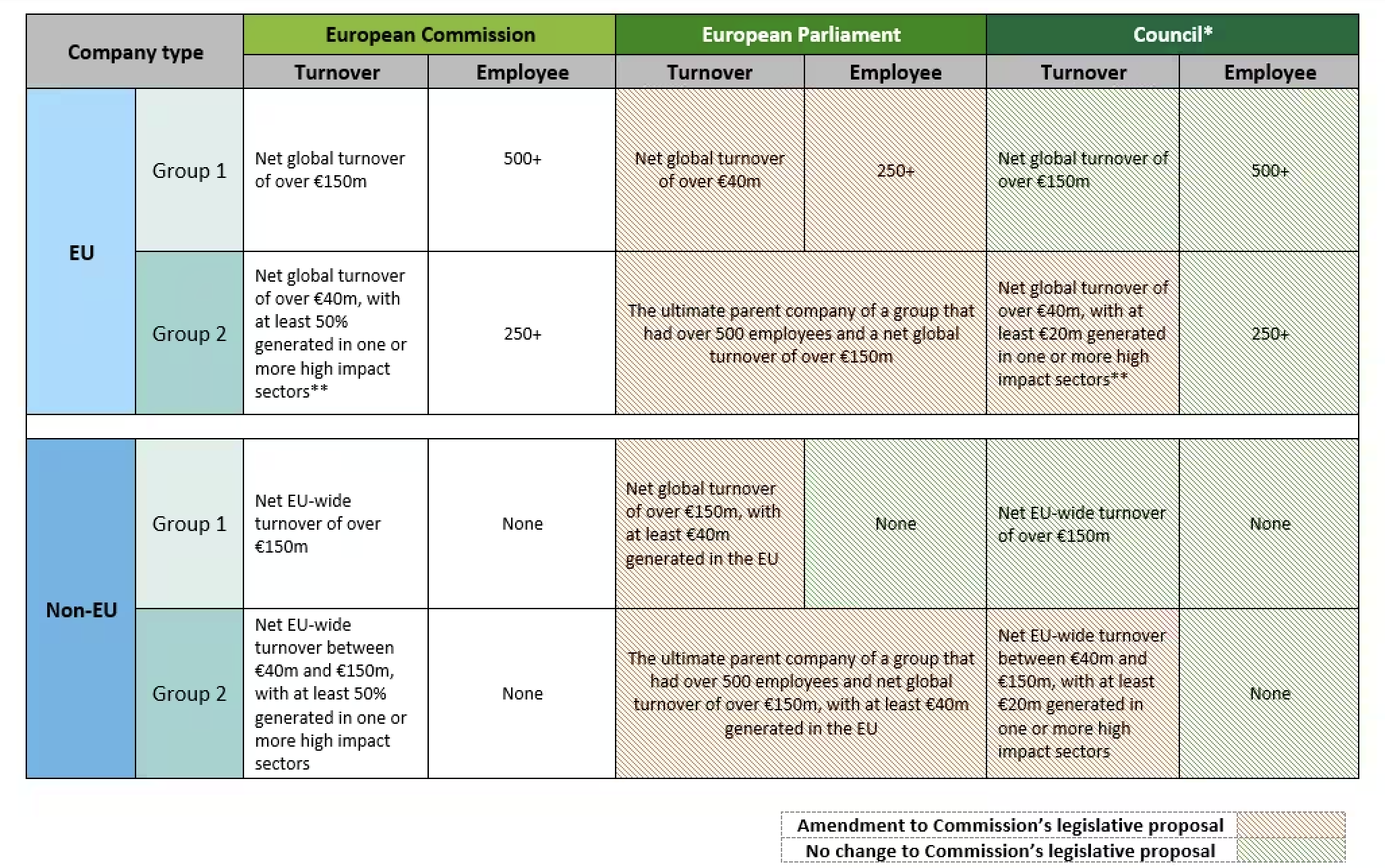

Applicability: In terms of applicability, the scope of the CSDR primarily extends to …

> Companies listed on EU regulated markets whose balance sheet total assets are greater than €20 million;

> “Large” EU companies (including EU subsidiaries of non-EU parent companies) that meet two of the following criteria: (i) have at least €20 million in total assets; (ii) have at least €40 million in net turnover; and/or (iii) have at least 250 employees (average) during the fiscal year; and

> Non-EU groups (including U.S. headquartered groups) that have significant activity in the EU and have net turnover in the EU in two consecutive financial years that is more than €150 million; and have at least: (i) one branch in the EU that has a net turnover of at least €40 million or (ii) one subsidiary in the EU that meets certain thresholds set out in the CSRD, including being a large company or a listed small and medium enterprise in the EU.

* The CSRD also applies to listed small and medium-sized enterprises; however, these SMEs will be subject to lighter reporting requirements and will benefit from an opt-out until 2028.

Materiality: Another important takeaway when it comes to the CSDR is materiality, with the legislation mandating that companies will need to identify material sustainability impacts, risks and opportunities by way of a “double materiality” assessment, which “broadens the concept of materiality from a sole focus on financial materiality to one that includes a view of your impact on stakeholders and society,” per PwC. The consultancy states that this assessment requires viewing materiality from two perspectives …

> Financial materiality: This “outside in” view focuses on how sustainability matters may pose either a prospective material risk or opportunity that could affect a company’s financial performance and position over the short, medium and long term. Sustainability matters are considered material for primary users of a company’s financial reports if omitting or misstating the information could influence the users’ decisions.

> Impact materiality: This “inside out” view focuses on the actual or potential short, medium and long-term impacts on people or the environment that are directly linked to a company’s operations and its value chain. These impacts can be both positive and negative.

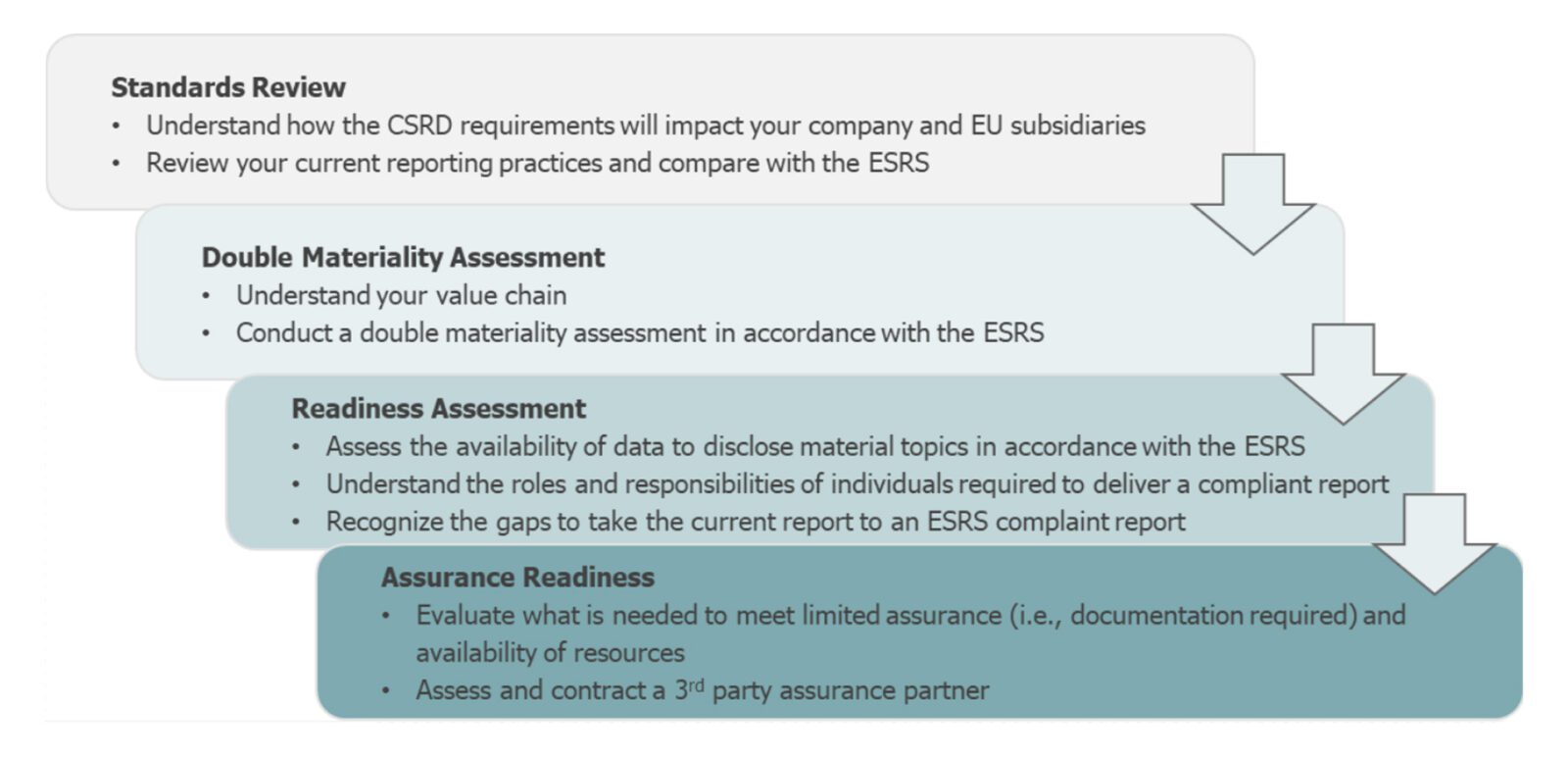

Immediate Action Steps: The following (courtesy of Georgeson) is a proposed guide for steps that companies slated to be impacted by the CSRD could plan for compliance with the legislation …

Timing: The CSRD is slated to be implemented into national law by each EU member state by July 6, 2024, and companies that meet the reporting requirements will have to submit their first report of aligning with CSRD by Jan. 1, 2025.

Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (“CSDDD”) – Aimed at “enhanc[ing] the protection of the environment and human rights in the EU and globally” by requiring companies to assess the ESG-centric risks in their operations, the CSRDDD mandates that large EU companies must conduct environmental and human rights due diligence across their operations, subsidiaries, and value chains.

Applicability: The main categories of companies that will fall within the scope of the CSDDD are …

> Large EU companies with a net global turnover of over €150 million in the last financial year and more than 500 employees;

> EU companies with more than 250 employees and a net worldwide turnover of more than €40 million, provided at least 50% of this turnover was generated in a high-impact sector. (“High-impact” is defined by the European Commission as manufacturing textiles, engaging in various agricultural activities, and the extraction of mineral resources”;

> Large non-EU companies with an EU-wide revenue of over €300 million; and

> Non-EU companies that generate a net turnover of more than €40 million in the EU, provided at least 50% of worldwide turnover was generated in a high-impact sector.

Impacts: In terms of disclosure, the CSDDD mandates that in-scope companies identify and address potential and actual adverse human rights and environmental impacts across their own operations, subsidiaries, and value chain. To do this, the directive requires companies to follow six specific steps (outlined below courtesy of Deloitte), which mirror the steps defined by the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct …

Reflecting on the implementation of the CSDDD, Deloitte stated in a note that expects the compliance burden “to be significant, especially for companies with extensive, international value chains,” making the 2027 implementation date “challenging.” The consultancy also asserted, “The requirements of the CSDDD are expected to dovetail with CSRD and will also be the first piece of EU legislation that mandates companies to adopt a climate transition plan. Companies should consider whether they are looking at sustainability reporting holistically and understand the links between the CSRD and other regulatory requirements, such as the CSDDD, or the EU Taxonomy Regulation.”

Timing: The CSDDD’s requirements are expected to apply to the largest EU companies (1,000 or more employees) beginning in mid-2027 and one year later for large EU companies (500 or more employees). The provisions will not apply to non-EU companies in scope until three years from when the CSDDD comes into effect (i.e., 2027 at the earliest).

The timeline is currently unclear in light of the fact that the EU Council failed to endorse the CSDDD during a meeting of the Committee of Permanent Representatives on February 28, a move that is being characterized as a significant setback for the legislation. Reuters reports that “not enough envoys from the 27 EU countries backed the law for it to proceed,” with the bill needing “a ‘qualified majority’ of 15 EU countries representing 65% of the EU population … before a final vote in the European Parliament, where lawmakers were expected to support it.”

> CSDDD and CSDR: The CSDDD and the CSRD both are largely based on the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the UN guiding principles on Business and Human Rights as international due diligence frameworks.

In two bills that focus more on the ways in which companies can – and cannot – market “green” or other “environmentally-friendly” products/services, the EU has introduced the Green Transition Directive and the Green Claims Directive.

Green Transition Directive (“GTD”) – The GTD amends existing consumer laws on unfair commercial practices in the EU (namely, the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive and the Consumer Rights Directive) to specifically capture environmental claims. According to the European Council, the GTD “will protect consumers against misleading ‘green’ claims, including unfair claims about carbon offsetting,” while also “clarifying [companies’] liability in cases of information (or lack of information) on early obsolescence, unnecessary software updates or the unjustified obligation to buy spare parts from the original producer and improving the information available to consumers to help them make circular and ecological choices.”

The GTD was approved in principle by the EU Council and Parliament in September 2023, was endorsed by the European Parliament on January 17, 2024, and was formally adopted by the EU Council on February 20, 2024. “After being signed by the president of the European Parliament and the president of the Council,” the EU Council says that the directive will be published in the Official Journal of the European Union and “will enter into force on the twentieth day following its publication.”

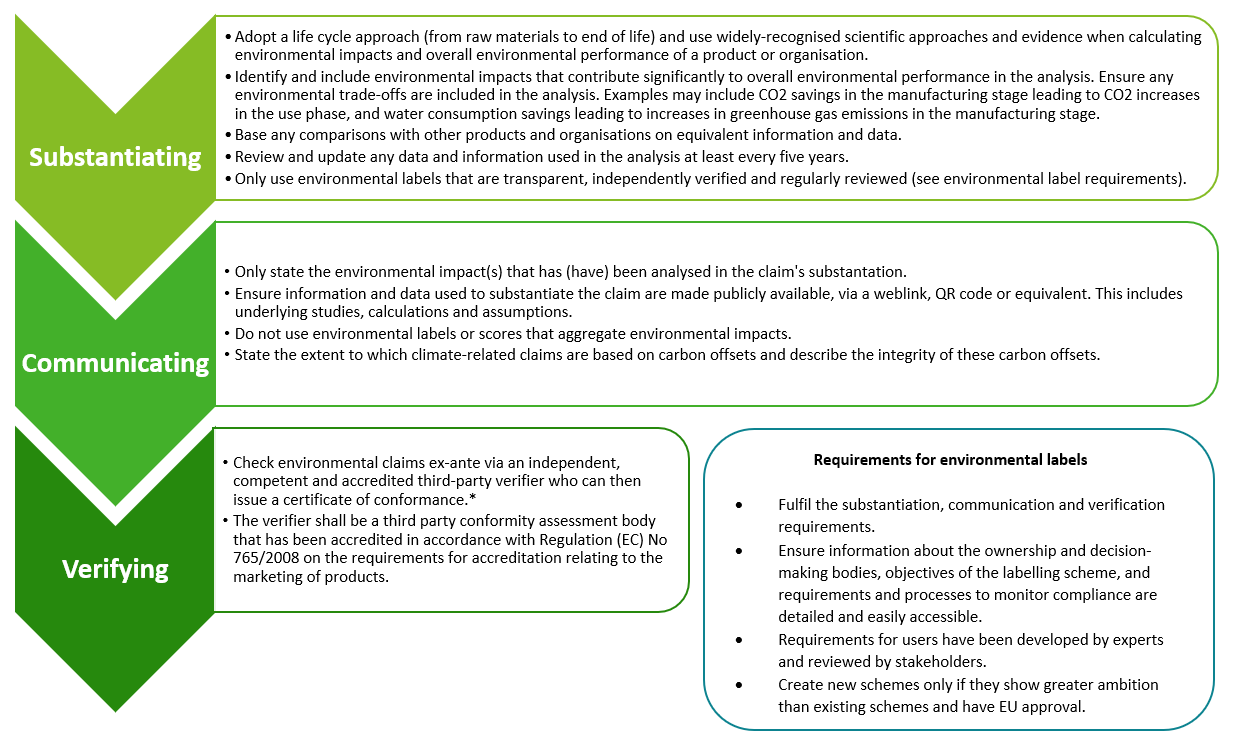

Green Claims Directive (“GCD”) – The GCD, a proposal for which was adopted by the European Commission back in March 2023, endeavors to stop companies from making misleading claims about environmental merits of their products and services, and to ensure that consumers receive reliable, comparable and verifiable environmental information on products.

Focused primarily on consumer-facing environmental claims that companies make about their products/services, the GCD – which will apply to the vast majority of EU operating companies – will introduce new minimum substantiation requirements and mandate that companies making environmental claims communicate them accurately and have them verified by a third-party before being published. Additionally, the GCD will prohibit the use of generic environmental claims (such as “eco-friendly”, “eco”, “green”, “sustainable”, “made of 100% recycled plastic” and “climate neutral”) unless they are based on demonstrated environmental performance.

In a note, Cooley states that the GCD is part of “a clear drive to create stricter rules on green claims and increase the enforcement of greenwashing in the EU, which has historically not been approached in a consistent way across the 27 EU Member States. Companies that wish to use green claims on their products will now need to consider them very carefully and make sure they have carried out assessments to back them up and had them verified and certified by an independent certification body.”

Meanwhile, Travers Smith notes that both the GTD and the GCD – paired with existing litigation on the false advertising front – “illustrate the high level of concern among governments and regulators,” as well as consumer plaintiffs, “about misleading green claims, [and] in particular, they further underline the need to ensure that any such claims are supported by robust evidence – even to comply with the existing regulatory frameworks in the EU and the United Kingdom.”