Artificial intelligence (“AI”) artwork generators garnered a notable amount of attention in 2022 and have continued to do so this year. One of the mostly widely referenced AI art generators, DALL-E – which was first introduced in January 2021 – is touted as capable of “creat[ing] original, realistic images, and art” based on a user-provided text description. In other words, if you type in a combination of words, DALL-E can render an image based on that input using machine learning and supporting software. Other image generators, such as Stable Diffusion, operate similarly, creating images that look like oil paintings, drawings, photos, etc. based on a user’s prompts, or music (based on genre, length, and mood inputs) with little – if any human – contribution. Unsurprisingly, the ability of these AI systems to generate artistic outputs presents legal questions, namely, in the copyright vein.

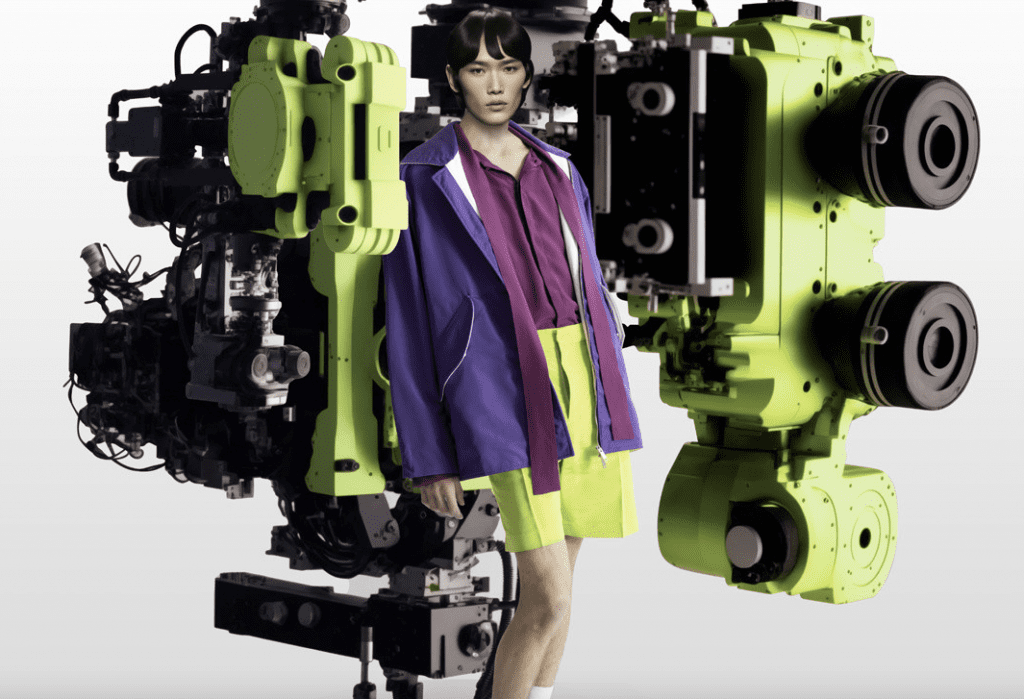

As AI takes on a larger role in creation, as reflected in AI-generated ad campaigns coming from brands like Valentino and spirits company Martini, “It is becoming increasingly important to determine whether there are intellectual property rights [at play when it comes] to substantially machine-generated works and, if so, who owns them,” Lewis Rice’s Kirk Damman, Benjamin Siders, Kathleen Markowski Petrillo, and Olivia Dixon stated in a note this summer. Primarily, there is the issue of copyright protection in the U.S., which has been reserved for works of human authorship, and thus, poses questions about whether images entirely created by AI could be deemed eligible. (Registration is significant, as it is a prerequisite for filing a lawsuit for copyright infringement.)

“Courts have in the past decided cases revolving around the ‘human authorship’ requirement of the Copyright Act (e.g., pictures taken by monkeys are not copyrightable because they are not created by a human),” according to Mesh IP Law’s Michael Eshaghian. But until recently, courts had “not been directly faced with the question of whether AI-generated works are copyrightable.” However, that is changing (and the law could be changed – by courts or Congress) thanks to the lawsuit that Stephen Thaler waged against the Shira Perlmutter and the U.S. Copyright Office in the wake of the U.S. Copyright Review Board confirming that copyright protection only extends to works of human authorship.

Beyond the threshold issue of registrability, other questions abound, according to Morrison & Foerster’s Heather Whitney and Tessa Schwartz, such as: (1) to what extent “can a human use AI tools in the creation of a work before that work will no longer be considered a work of a human author” and (2) “whether the outputs from certain deep learning AI systems can infringe copyrighted works.” In terms of AI-generated outputs, they assert that aside from violating the exclusive rights of the copyright owner (from unauthorized copying to the creation of derivative works), courts also require that any alleged infringement “result from the defendant’s ‘volitional conduct.’” This is likely to prompt debate over “whether infringement occurs where outputs of sophisticated deep learning AI systems are attenuated from anyone’s (i.e., a human’s) volitional act.”

Another question: Whether the use of copyrighted materials as training data for machine learning – OpenAI, the research lab behind DALL-E, trained the tool by scraping and analyzing more than 650 million images – qualifies as fair use. While the Ninth Circuit reaffirmed in April 2022 that “scraping publicly available data from internet sources does not violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act,” Greenberg Glusker’s Aaron Moss noted that “no court has yet decided whether the ingestion phase of an AI training exercise constitutes fair use under U.S. copyright law.” A fair use argument might be plausible, he states, citing the outcome in Authors Guild, Inc. v. Google, Inc., as “AI tools are not copying images so much to access their creative expression as to identify patterns in the images and captions,” and at the same time, “the original images scanned into [the AI platforms’] databases … are never shown to end users.”

That question will likely be at the center of another newly filed lawsuit, the one that artists Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan, and Karla Ortiz filed against DeviantArt, Midjourney, and Stability AI, accusing them of copyright infringement in connection with the use of their artwork to train AI generators to create “new” art in response to user prompts. Getty has also said that it “commenced legal proceedings [this week] in the High Court of Justice in London against Stability AI claiming Stability AI infringed intellectual property rights including copyright in content owned or represented by Getty Images.”

And still yet, an additional question that has already arisen centers on ownership: Assuming that AI-generated works are deemed to be protectable under copyright law in the U.S., how will the resulting rights be assigned? So far, this question has largely been contracted away by the entities offering up such AI art-generating services. DALL-E’s terms state that “as between the parties and to the extent permitted by applicable law, you own all Input, and subject to your compliance with these Terms, OpenAI hereby assigns to you all its right, title and interest in and to Output.” (This appears to differ from previous terms that Quartz reported in September 2022 as stating, “‘OpenAI owns all generations’ created on the platform, and only grants users the right to use and claim copyright on their AI-generated imagery.”)

Meanwhile, Midjourney – which boasts a proprietary AI program that creates imagery, such as Martini’s latest campaign, from text descriptions – similarly grants users ownership of “all assets you create” with its AI, subject to a potential license granting Midjourney the right to display outputs for others to “view and remix.”