Over the past decade, “the rapid development of social networking sites, such as Facebook, Twitter, [Instagram, and Snapchat], has caused profound changes in the way people communicate and interact.” This is what Dr. Igor Pantic reported in a study published in 2014 by the U.S. National Library of Medicine at the National Institute of Health. While the likes of Facebook and Instagram give rise to “numerous advantages in terms of increasing connectivity, sharing ideas, and online learning,” these platforms and their combined billions of users – which are still a relatively new phenomenon – and the potential connection between them and psychiatric diseases poses a serious public health concern in the eyes of many mental health professionals across the globe.

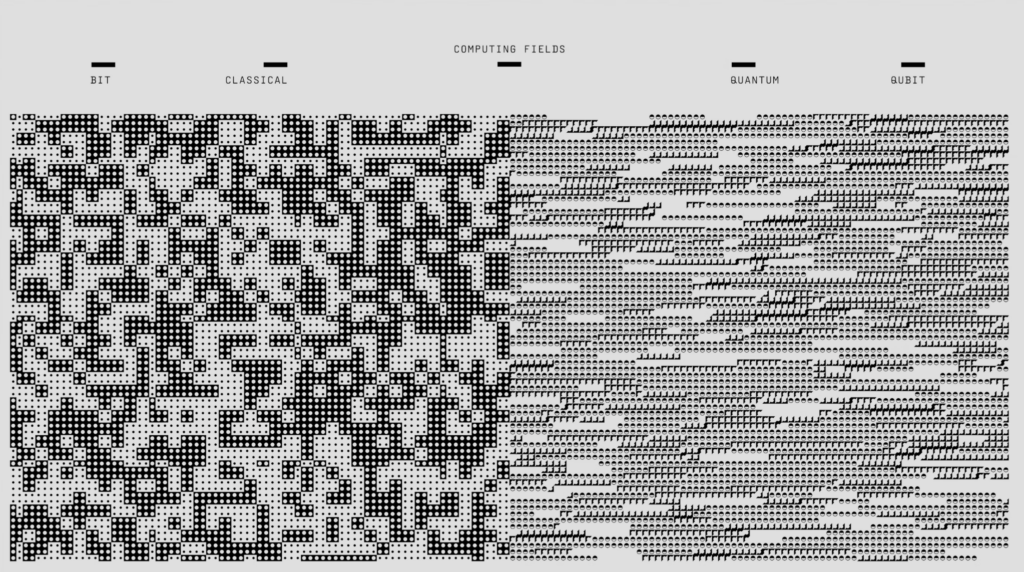

Beyond the arguably obvious inverse relationship between wellness and prolonged social media usage (and all of the hyper-comparison that comes along with it), there is a more foundational change at play: “Nowadays, social networking does not necessarily refer to what we do,” whether it be engaging in activity “on traditional sites, such as Facebook, [or] more socially-based online gaming platforms and dating platforms, all [of which] allow users to connect based on shared interests.” Instead, it is more aptly characterized as an integral part of “who we are and how we relate to one another.”

This assertion is at the core of recent scholarship put forth by Daria Kuss, a Chartered Psychologist, Chartered Scientist, Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Nottingham Trent University, and Mark D. Griffiths, a Chartered Psychologist and Distinguished Professor of Behavioral Addiction at the Nottingham Trent University. In their paper, Social Networking Sites and Addiction, the duo makes the important distinction between considering social media a passive element of life in 2018, and identifying it as “a way of being and relating.”

“A younger generation of [individuals] has grown up in a world that has been reliant on technology as an integral part of their lives, making it impossible to imagine life without being connected. This has been referred to as an ‘always on’ lifestyle,” they state. “It’s no longer about on or off, really. It’s about living in a world where being networked to people and information wherever and whenever you need it is just assumed.”

According to Drs. Kuss and Griffiths, this has two important implications. First, “Being ‘on’ has become the status quo,” and second, “There appears to be an inherent understanding or requirement in today’s technology-loving culture that one ‘needs’ to engage in online social networking in order not to miss out, to stay up to date, and to connect.”

This “need” falls somewhat neatly, they say, within the basic spectrum initially described in Maslow’s hierarchy, referring to the psychological theory proposed by Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation.” In that work, Maslow points to “physiological,” “safety,” “belonging and love,” “esteem,” and “self-actualization” to describe the pattern through which human motivations generally move – and Kuss and Griffiths asserts that empirical research supports a finding that social networking meets many of these needs.

They write, “Safety needs are met by social networking being customizable with regards to privacy, allowing the users to control who to share information with. Associative needs are fulfilled through the connecting function of [social networking sites], allowing users to ‘friend’ and ‘follow’ like-minded individuals. The need to estimate is met by users being able to ‘gather’ friends and ‘likes’, and compare oneself to others, and is therefore related to Maslow’s need of esteem. Finally, the need for self-realization, the highest attainable goal that only a small minority of individuals are able to achieve, can be reached by presenting oneself in a way one wants to present oneself, and by supporting ‘friends’ on those [social networking sites] who require help.”

“This may offer an explanation for the popularity of and relatively high engagement with [social networking sites] in today’s society,” per Kuss and Griffths. It also gives rise to the question: Is our collective social media addiction the result of the technology itself (and the ease with which we can access such networks by way of mobile technology and tablets, etc.) or “is it more what the technology allows [us] to do”?

It has been argued previously, including by media scholars, Kuss and Griffths state, that “the technology is but a medium or a tool that allows individuals to engage in particular behaviors, such as social networking and gaming, rather than being addictive per se.”

“Following this thinking,” they assert, “one could claim that it is not an addiction to the technology, but to connecting with people, and the good feelings of appreciation that [social media interactions] can produce.” In short: Social media is part of who we are in 2018 and for better or worse, we are all addicted to “likes.”