A new trademark lawsuit over a “copycat” political website could have some broad implications, including for brands in the consumer goods space. In the complaint that it filed with a federal court in Delaware on Tuesday, No Labels claims that the unaffiliated NoLabels.com Inc. (the “defendant”) is on the hook for not only using its trademark-protected name but also “creating and is actively promoting a website designed to mimic No Labels’ legitimate website for the purpose of deceiving the public, including voters.” All the while, No Labels alleges that the defendant has purchased advertisements on Google in order to “steer individuals who are seeking information about No Labels … to [its] infringing website.”

Setting the stage in the newly-filed case, No Labels asserts that in an attempt to “trade on No Labels’ goodwill and deceive individuals about the candidates, platform, and advocacy of No Labels,” NoLabels.com is hosting a website hosted at the URL nolabels.com that is “intentionally designed to mimic the look and layout of the No Labels website.” Specifically, the Washington, DC-based public policy non-profit claims that the defendant’s website makes use of “a black banner with ‘NO LABEL’ in thick white block text at the top, an oval shaped button at the top right where users may donate or sign up for mailing list, and a similar color scheme of black, white, and yellow.”

The defendant goes further than such “visual similarities” on its website, per No Labels, by “repeating key phrases” used by No Labels, such as the phrase “commonsense majority,” and making “deceptive use of photographs of candidates who appeared at [a] No Labels Convention, including under the heading ‘NoLabels.com Leaders,’ to suggest (falsely) that No Labels endorses or supports those candidates.” Still yet, No Labels asserts that the defendant “explicitly states” on its website that it is “a hub for No Labels Party supporters to foster discussions and solutions” in a move to “directly and misleadingly link the website with No Labels.”

And all the while, No Labels argues that the defendant has maintained a Google Ads campaign to improve the search result ranking of the infringing domain, encouraging viewers to “Join NoLabels.com Today.” The ads, which “in and of themselves constitute trademark infringement,” according to No Label’s counsel at Nixon Peabody, “are clearly designed to misdirect individuals seeking information about No Labels to the infringing website and its misleading content.” (On the keyword advertising issue, it is worth noting that while no shortage of the many, many trademark lawsuits filed over competitive keyword advertising have settled, courts have sided with the defendants in various cases.)

While No Labels insists that it “does not object to third parties referencing [it] when commenting on [its] positions or candidates” and similarly does not seek to “stifle free political discussion or competing points of view,” it says that the defendant “cannot … use the No Labels registered trademark, and language and imagery evocative of the legitimate No Labels website, to attract internet traffic to an infringing website that is designed to mislead and confuse the public, including voters and donors, in order to harm No Labels.”

With the foregoing in mind, No Labels sets out claims of cybersquatting and trademark infringement/false designation of origin, and is seeking injunctive relief, an order requiring the defendant to transfer the nolabels.com domain to No Labels, and monetary damages.

Other Cases Over Website Trade Dress

While certainly not a fashion or luxury-specific matter, the case is, nonetheless, one worth paying attention to in light of the importance of companies providing consumers with compelling and distinctive e-commerce (and m-commerce) experiences, and the desire of brands to seek protection to ensure that competitors are not co-opting such designs. Not the first case to claim trademark (or trade dress) infringement in connection with the alleged copying of a website design, two (somewhat) similar suits on the consumer goods front provide insight when it comes to the protectability of (or lack of protections for) website designs …

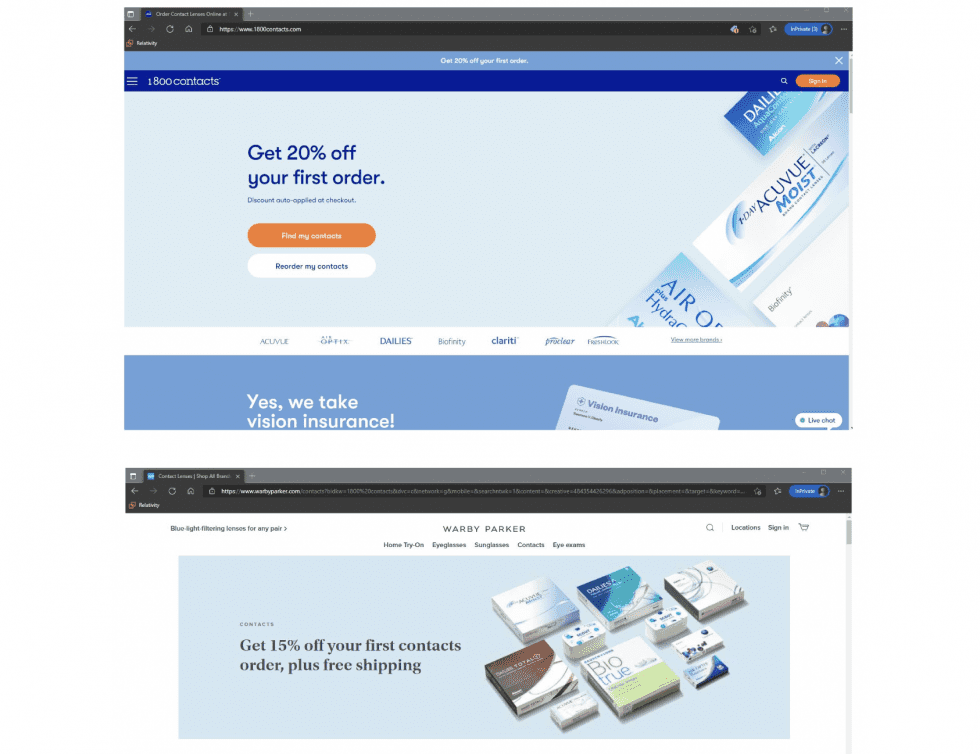

1-800 Contacts v. Jand, Inc. d/b/a Warby Parker – In this case, Warby Parker was sued for allegedly attempting to confuse consumers into believing that its products are affiliated with those offered up by 1-800 Contacts by using 1-800 Contacts’ trademark (including by way of a Google keyword campaign) while also adopting a website landing page that allegedly “mimics the look and feel of the 1-800 Contacts website.”

Before the court ultimately sided with Warby Parker (on the basis that consumers were unlikely to confuse the two brands’ marks, especially given that consumers are likely to pay close attention to the source of their eyewear products and since Warby Parker’s name is clearly displayed on its allegedly infringing website), the buzzy eyewear brand pushed back against 1-800 Contacts’ trade dress claims. In particular, Warby took issue with 1-800 Contacts’ assertion that it “possesses a valid, protectable proprietary interest in the ‘look and feel’” of its website – namely, “the prominently featured shade of light blue on its homepage,” as well as “the light blue rectangular shaded box that spans most of the screen in a horizontal configuration and displays representative contact lens product packages to the right of a discount offer to ‘Get 20% off your first order.’”

According to Warby Parker, 1-800 Contacts lacks valid trademark rights, as the design of its site has not acquired distinctiveness. Warby Parker further argued that 1-800 Contacts does not maintain rights in the appearance of its website, in part, because “multiple companies selling contact lenses online use the color blue and/or the same general layout as referenced [by 1-800 Contacts] in connection with their online promotion, advertisement, and sale of contact lenses,” making it so that the design is not distinctive and has not acquired secondary meaning in the minds of consumers.

And to prove its point, Warby Parker pointed to “multiple third-party websites that present some combination of … (i) a blue and/or a rectangular shaded box that spans most of the screen; (ii) a display of representative contact lens products; and (iii) and a discount offer.”

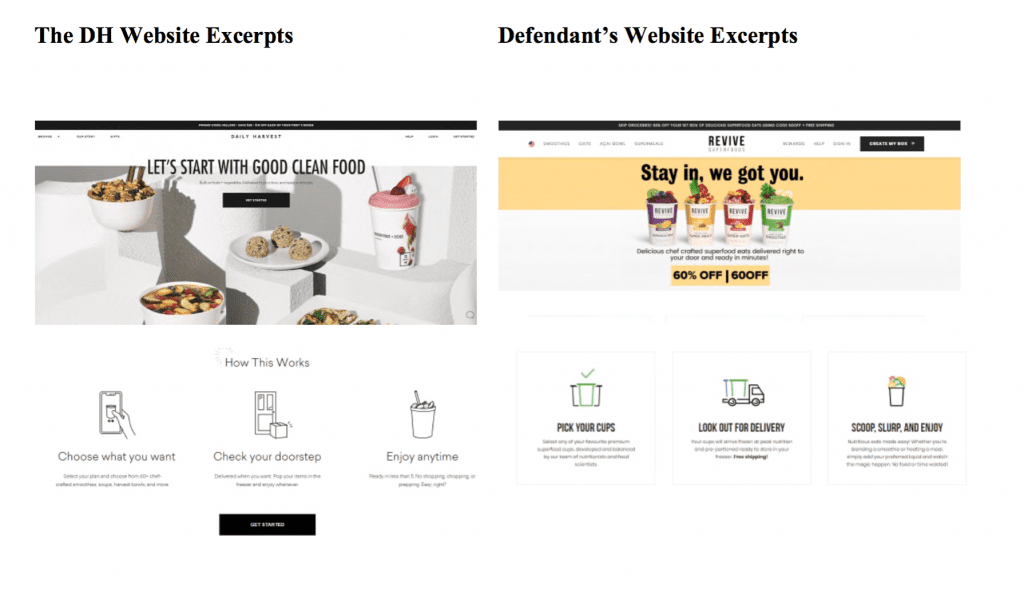

Daily Harvest v. Revive Organics – Before 1-800 Contacts filed suit against Warby Parker, Daily Harvest took on Revive Organics, accusing its fellow frozen food subscription company of engaging in trademark infringement by allegedly adopting “an identical and confusingly similar website design, content, [and] product packaging,” among other things. In the case that it filed in April 2020, Daily Harvest argued that it maintains rights in, among other things, the “unique and inherently distinctive” in the elements that make up its website – from the layout and some of the language to the “user shopping experience and interface design.”

(Note: Daily Harvest’s argument about the protectability of its site is in line – at least at a high level – with existing case law, such as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit’s 2014 decision in Fair Wind Sailing v. Dempster, holding that the defendant had infringed the trade dress of the plaintiff’s website. Around the same time, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California determined in Ingrid & Isabel, LLC v. Baby Be Mine, LLC that the total look and feel of a website used to market and sell products and services can constitute protectable trade dress under the Lanham Act.)

Before the case settled, Revive asserted that Daily Harvest’s alleged website trade dress is not distinctive, “meaning that the design of the website itself is not an indicator of source.” Aside from the Daily Harvest name, Revive argued that Daily Harvest’s “website is a compilation of common ornamental and functional features that are neither inherently distinctive nor have they acquired distinctiveness.” In case that is not enough, Revive claimed that Daily Harvest’s alleged website trade dress is invalid because “the vast majority of its listed elements are functional and, even when combined with ornamental elements, cannot serve as part of its protectable trade dress.”

And “even if Daily Harvest could prove a protectable trade dress in its website,” Revive argued that it cannot show that consumers visiting Revive’s website are likely to confuse its products with Daily Harvest’s. Pointing to a 2004 decision from U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in the Louis Vuitton Malletier v. Dooney & Bourke case, Revive asserted that “the prominent use of … brand names throughout [the respective companies’] websites is itself powerful evidence that confusion is unlikely,” which is part of what the court ultimately found in the 1-800 Contacts v. Warby Parker case.

The case is No Labels v. NOLABELS.COM INC., 1:23-cv-01384 (D. Del.).